Steve Cain is a retired wildlife biologist who spent his 25-year career researching and protecting the wild species of Grand Teton National Park. In his seasonal column, Field Notes, Steve shares his insight on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s incredible wildlife.

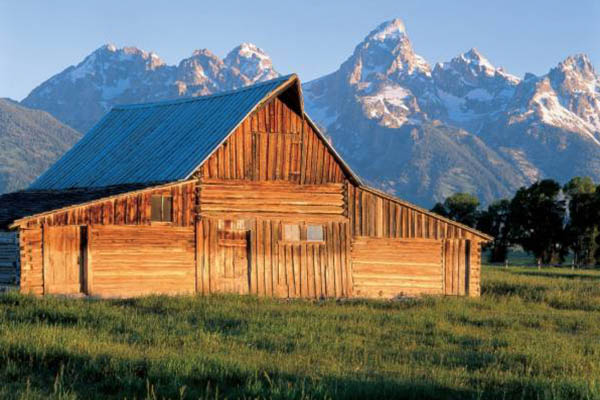

Natural rhythms continue in Grand Teton National Park despite Covid-19 pandemic disruptions in all of our lives. As spring unfolds, snow is replaced by emerging green foliage, streams and rivers swell, animals migrate, and signs of reproduction become prominent.

Annual reproductive output and trends are key metrics for wildlife managers, who use them to gauge animal population health. For biologists, this means fieldwork and generally the busiest time of year. As the season progresses into early summer, determining how many nestling raptors are produced and survive, counting calves and fawns of bison, moose, and pronghorn, and visiting breeding bird survey routes are part of a large menu of chores that park staff tend to each year. Resulting data help inform long-term conservation stewardship programs.

As a wildlife ecologist in the park for 26 years, collecting this information was the lifeblood of my existence. It provided a wealth of rich, often sublime personal experiences that never let my lifelong passion for wild things and landscapes wane, and helped provide meaning to unavoidable administrative tasks and the high stakes wildlife politics that were also parts of my job.

This time of year I often think of an April morning in the mid-1990s, when I headed out in the dark to get in position for a sage-grouse count at one of the park’s many leks. My assignment was part of a coordinated, park-wide assessment of sage-grouse with information dating back to the 1950s that is still conducted today.

A short, headlamp-assisted hike past some freshly-dug badger holes brought me to a familiar observation site as light just began to show on the eastern horizon—perfect timing. Readying my spotting scope and thermos of coffee, close enough to where I knew the grouse would be but far enough to assure no disturbance, I sat absolutely still. Careful not to let my parka ruffle, I focused all my attention on listening as the landscape began to stir. Though still a bit too dark to see, I could already hear the hollow popping sounds male sage grouse make to attract females for breeding. And as the sun rose and light invaded the last of night, a lone meadowlark called nearby, shadowed by playful notes of mountain bluebirds. I smiled taking in these classic indicators of an end to the long Jackson Hole winter.

A pack of coyotes yip-howled to the west as I turned my attention to the grouse, now dimly visible. It had rained the night before, creating fog and low clouds that hugged the ground and compromised visibility. But as the sun crested the Gros Ventre range, viewing conditions improved and I began my counting routine. This entailed tallying grouse numbers during repeated scans of the entire lek, alternating with scope and binoculars, until birds dispersed from the area, usually an hour or so after sunrise. Numbers varied during the survey as the birds moved among sagebrush, but the highest count of the morning was the data point of interest.

Just minutes into my task, the breeze shifted almost imperceptibly and the faint but unmistakable sounds of calling elk to the southeast got my attention. I remained focused on the grouse, but it became apparent that the elk were getting closer and that there were many of them. For a minute or two between scans I’d look up, hoping to get a glimpse of them, but low clouds and mist blocked my view.

A scan or two later the sun penetrated a narrow opening as the clouds and fog slowly dissipated. I’d been sitting nearly motionless in the subfreezing dawn for over an hour by then and welcomed the sudden warmth. This justified a short break in my scanning, I told myself, so I turned my scope in the direction of the elk, now louder than ever. I found them instantly. A large group of cows and calves were moving slowly but deliberately north through the sagebrush steppe, single file, acting out a primeval tradition of migration between winter and summer ranges. It was a moving vision that only got more intense. As I scanned the group from north to south and my scope lined up with the sun, the elk’s warm breath became backlit in the cold morning air, rising at regular intervals like whale spouts on water. Just a tad further south, the procession lined up with the silhouette of the Sleeping Indian—Sheep Mountain—still gloriously shrouded in snow that took on a pinkish hue in the morning sun. I estimated at least 1,000 animals and couldn’t see the end of the line.

The coyotes howled again as I refocused on the grouse, with a surge of exhilarating but peaceful emotion running through me. I continued counting, thinking I had the best job in the world. I felt I had been transported to a time thousands of years before, when nature’s forces ruled unmarred by modern human endeavors. I was just a speck on one of most exquisite, awe-inspiring landscapes in the world, witnessing unimaginable ecological beauty. To this day I maintain a clear image of that scene and the feelings I had there, some 25 years later.

Preserving the natural processes that provide human experiences like this is what the national parks are all about. During these strange times, I take great solace in knowing they await us all, once the parks open back up and our lives return to more familiar rhythms.