Steve Cain is a retired wildlife biologist who spent his 25-year career researching and protecting the wild species of Grand Teton National Park. In his seasonal column, Field Notes, Steve shares his insight on the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem’s incredible wildlife.

Grizzly bear and cub. Photo by Gary Pollock.

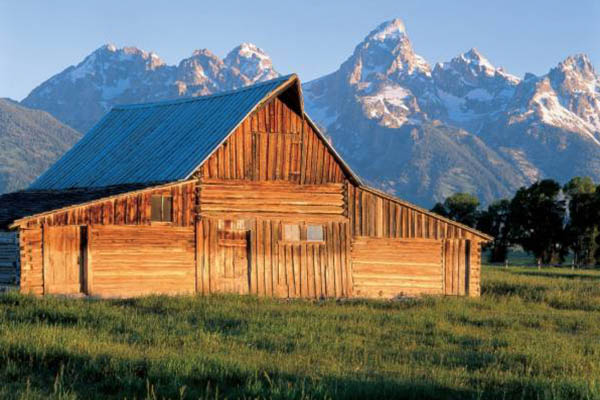

Longer days, melting snow, bold patches of green, and the soul-warming sounds of mountain bluebirds, meadowlarks, and osprey signal the arrival of spring in Grand Teton National Park. Spring in the Rockies is a time of renewal, dramatic season change, and the business of reproduction among wildlife. In this high elevation, interior climate where summers and associated growing seasons are short, animal reproductive strategies focus on getting the job done through a variety of means.

Broadly speaking and at opposite extremes of a wide spectrum, animals reproduce by either having lots of offspring of which few survive, or few offspring of which most survive. The former tend to be smaller animals with short gestation periods and generation cycles, whose young require little parental care. The latter tend to be large bodied with long gestation periods and generation cycles, whose young require extensive parental care. Among mammals, small, short-lived rodents are at one end of the scale, while large, long-lived primates, carnivores, and pachyderms are at the other. Similar relationships are found in birds, but among all animals there are exceptions, and strategies can combine characteristics of both approaches.

In Grand Teton, deer mice and grizzly bears are opposites. Deer mice are short-lived, prolific breeders that have multiple litters and flood the landscape with offspring to maximize the chance of survival. Long-lived grizzlies, on the other hand, have an exceptionally low reproductive rate, raising just 2 offspring every 3 years on average. Mice require little parental investment and have huge mortality rates, while young grizzlies get extensive instruction and have much higher survival rates. Wolves, which have a moderate lifespan, a relatively high reproductive rate and invest heavily in offspring, combine characteristics of both mice and grizzly bears.

Among birds, long-lived bald eagles, whose few offspring require extensive parental care, are similar to grizzly bears. They meet the needs of a long nesting cycle by starting early—breeding in March and laying 1-3 eggs in April—and feeding nestlings that fledge in August throughout the spring, summer, and fall. Trumpeter swans, up to twice the weight of eagles and the heaviest birds in North America, use a similar tactic. But during some cold years at our elevation, they barely get offspring on the wing before nesting waters freeze. Smaller, shorter-lived birds with brief nesting cycles, like warblers and chickadees, wait until warmer weather and abundant food is available before nesting. And because their breeding cycles are short, some smaller birds can pull off a second nesting cycle if the first one fails, increasing their odds of successful reproduction each year.

Next time you are in the park, take some time to observe and contemplate the many reproductive schemes that have evolved in our magnificent wildlife. Bring your binoculars and spotting scopes, and please remember to give all animals the space and respect they deserve during this sensitive period of their annual life cycle.