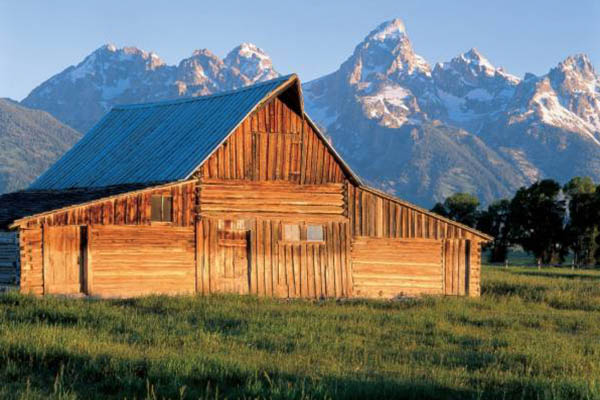

Photo by Ryan Sheets

Photo by Ryan Sheets

Winter in Jackson Hole was a bit slow in coming this year, but by mid-December it seemed to be revving up in good form. While winters can be tough on ill-prepared individuals, human or otherwise, our native fauna have endured thousands of Teton winters and have developed a variety of effective adaptations for survival in the process.

An evolutionary fork in the road akin to “should I stay or should I go?” describes two primary approaches of our wildlife to surviving winter: staying put versus migrating to warmer climes. Hummingbirds, osprey, warblers and scores of other species migrate long distances to escape winter’s cold and shortage of food. Winter-adapted, non-migratory chickadees, jays, eagles, and dippers, on the other hand, simply hunker down with the rest of us year around residents. Other animals that tolerate cold but are poorly adapted to snow employ shorter migrations, like pronghorn that move to the Pinedale area in winter, elk and deer that move to low elevations, and sage grouse that seek large, exposed sagebrush for cover.

Among those that stay, a few species actually harvest and cache summer foods to nourish them through winter’s darkest days. Pikas collect and stack grasses and forbs in “haystacks” during the short, alpine growing season for their use months later under deep, high elevation snow packs. Beaver cut willow, aspen and other sprigs during summer and deposit them in massive piles near their lodge’s under-water entrance. In winter beneath thick pond ice, they make periodic trips to these aquatic pantries, which sustain them until spring. Crafty Clark’s nutcrackers cache whitebark pine cone seeds in hundreds of locations in August and somehow remember where to find them in February.

Others, including yellow-bellied marmots, Uinta and golden-mantled ground squirrels, and black and grizzly bears, survive winters by stashing their calories as fat and sleeping through the coldest days of the year. Marmots and squirrels enhance their calorie conservation by lowering their body temperature to near ambient levels and slowing their metabolic rate to a crawl. These true hibernators contrast somewhat with bears, which lower their heart and respiration rates during winter, but maintain near-normal body temperature while denned. If disturbed, they can arouse and be fully alert in seconds.

Unlike bears, Canada lynx, wolverine, and cougars remain active all winter. Their relatively large, snow-adapted feet give lynx the advantage they need to overtake snowshoe hares, wolverine the capability to patrol huge home ranges in search of large and small prey or carrion, and cougars the finesse required to kill elk, deer, and bighorn sheep on their winter ranges. Wolves also have large feet, but live in packs and utilize the trails of other pack members to further ease winter travel in pursuit of prey.

These are just a few examples in a vast and amazing array of adaptations the park’s cold and snow-adapted animals depend on. Best of season’s cheer to you all, and don’t forget to keep your own adaptations—skis, snowshoes, hats and gloves—handy during the winter!